“Mrs. Smith is here to see you,” your receptionist says.

You wonder, “What’s up?” She doesn’t have an appointment, and while you know her socially, all your communication is with Mr. Smith.

You hang up, rush to the lobby, and find her visibly upset. Her husband was hurt. He’s in an overseas hospital, unable to make decisions. Mrs. Smith needs $20,000 wired to her bank account, and she wants the money now.

You can’t take her instructions, though. The account is in Mr. Smith’s name. In one numbing instant, you recall all the times you encouraged him to give her trading authority.

“Or better yet,” you counseled repeatedly. “Set up and fund a revocable trust. The assets bypass probate. And if anything ever happens to you, your successor trustee can make decisions for your family.”

But Mr. Smith, a charming southerner with a big personality, always found a reason to procrastinate: “I’m catching ‘em faster than I can string ‘em.”

Now the problem is on you.

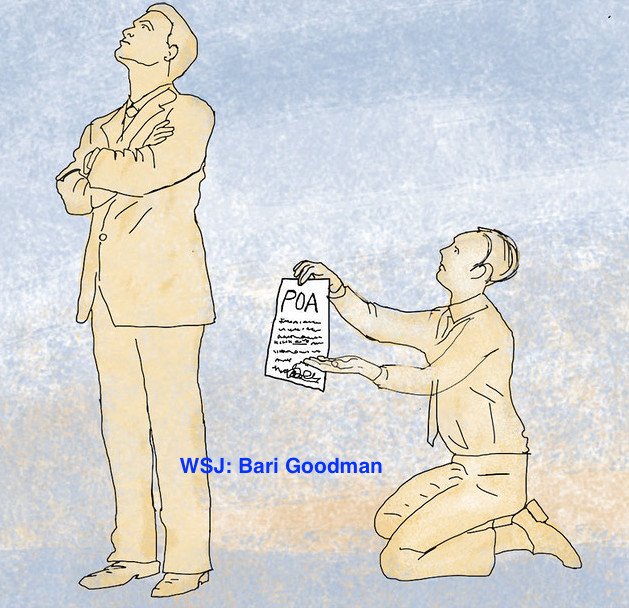

Or maybe not. Mrs. Smith fishes a legal form from her purse: “I have power of attorney.”

She waits in a conference room. You march back to your desk, reviewing the POA document en route. It’s the statutory form, drafted and approved by your state. It’s an original. It’s properly notarized.

Shouldn’t be a problem. Right?

When you reach the custodian, however, your nightmare gains momentum. The rep doesn’t even bother with logistics of getting the POA in time for money-transfer cutoffs.

She simply says, “We can’t accept that POA.”

Fast forward to the present: You’re probably thinking, “Most states require firms to honor their statutory POAs.” And you would be right.

Under New York law, for example, “No third party located or doing business in this state shall refuse, without reasonable cause, to honor a statutory short form power of attorney properly executed…”

Unfortunately, all too often, some firms will reject statutory POAs with a total disregard for the law.

Michael Roberts, president of the Reliance Trust Company of Delaware, first alerted me to the problem. His firm provides third-party trustee services to financial advisers across the country.

He attributed the spate of refusals to “untrained frontline personnel” or “risk aversion.” (Bad people do bad things with POAs; companies get sued.) And for proof, he emailed me several discussion threads from online legal forums.

The participating lawyers hailed from many different states. One after another, they expressed the same frustration–that financial institutions won’t accept their client POAs. They named big banks on both coasts, all of them with legions of financial advisers.

How can this be?

POAs are critical to wealth management. They’re one of the five pillars of estate planning, the others being wills, revocable trusts, health-care POAs and what I like to call “pull-the-plug directives.”

I asked Dave McCabe, a partner at Willkie Farr & Gallagher LLP, if he’s ever encountered this problem.

“If it’s happened once, it’s happened five hundred times,” says Mr. McCabe. While there are valid reasons to refuse a power of attorney, he usually hears one that isn’t: “I’m sorry. It’s not our form.”

I have a general power of attorney for my wife, the New York statutory short form. Mr. McCabe suggested I try using it to see what happens.

So I did.

Our local bank accepted it. Total disclosure: I’ve known the branch manager for years.

The custodian where we invest, however, was a different story. It’s a national organization. It works with lots of registered investment advisers. Ordinarily, I have nothing but praise for the company.

The representative said I could trade securities in my wife’s account–once his firm received and inspected the POA.

Fair enough.

But he added, “Outgoing transfers are capped at $10,000.”

“Run that by me again?”

I could withdraw more, he explained, after his firm sent notice to the address on the account and 30 days had elapsed. This “cooling-off” period, I assume, was created to protect clients from fraud or the various forms of bad behavior that sometimes accompany POAs.

Despite such good intentions, the custodian’s policy isn’t helpful if you’re the financial adviser with Mrs. Smith waiting in reception. She needs $20,000 now. You’re about to lose an account.

Continue reading on the Wall Street Journal.

The New York Times describes my novels as “money porn,” “a red-hot franchise,” and “glittery thrillers about fiscal malfeasance.” Through fiction I explore the dark side of money and the motivations of those who have it, want more, and will steamroll anybody who gets in their way.

The New York Times describes my novels as “money porn,” “a red-hot franchise,” and “glittery thrillers about fiscal malfeasance.” Through fiction I explore the dark side of money and the motivations of those who have it, want more, and will steamroll anybody who gets in their way.